atlantis vs. villano III (mask vs. mask lucha de apuestas match) (cmll, 03/07/2000)

some reflections on the meaning of Masks and the american reception of lucha libre

Old guys beating the shit out of one another is an integral subgenre of lucha libre, as it is in almost all variants of wrestling, but the match I’m writing about today particularly defies the stereotype best summed up by a classic Vince Russo-ism: “You can go to Japan and get all the lucha libres you want.” Last night I watched Atlantis against Villaino III from CMLL in 2000, a canonical lucha match that absolutely lives up to the hype for me and is quite possibly one of the greatest pieces of wrestling work I have ever witnessed. I find that whenever I try to plan these match blogs in advance, I stall out and my interest in a chosen subject gets stale, so I’m trying to chase the improvisatory feeling and write about whatever matches particularly strike me as soon after I watch them as I can. Like juice from a blade-job, sometimes you just have to let the words flow.

My earlier reference to Russo’s comment, snide ignorance swaddled in xenophobia, embodies so much of the response of mainstream American wrestling fans toward lucha libre specifically, but also almost anything that defies and denies the ignorant bliss they’ve come to expect from McMahon’s product: puro, European catch wrestling and more mat-based technical styles, intergender and women’s wrestling, deathmatch, old school Southern rasslin, the list is endless. In addition to how it has frequently been misunderstood by white corporate executives, lucha is derided by certain racists and nationalist chodes who still shout “USA'' during jaw-dropping gymnastic 6-man lucha tag matches at GCW shows, a refrain I unfortunately had the pleasure of hearing from a few assholes during the Hammerstein Ballroom show I got COVID at last January. Those jeers were a regrettable stain on the far-and-away heater highlight match of the night, the trios match between ASF/Bandido/ Laredo Kid and Arez/Demonic Flamita/Gringo Loco, some of the most physically gifted and aerodynamic athletes of any sport or physical performance all in the ring together going absolutely bonkers.

These are the same types who retweeted Top Dolla’s swipes at the Young Bucks, who use phrases like “spotfest” and “flippy shit” with a straight face, who call the artist known as “Kenny Olivier” a sissy, and who think Dwayne Johnson and The Undertaker are the greatest wrestlers of all time because of some equally bullshit kayfabe notion of “drawing power.” This certain profile of mark, so often insecure cishet men who sincerely “clap back” at Brandi Rhodes on Twitter and tune in only for the Dan Lambert and FTR segments of Dynamite, need wrestling to be something solid and separate from themselves, a strong tough Other to project strength upon when they feel threatened and insecure, a daddy whose validation they are constantly seeking, a sheen of glossy entertainment that exists within specific definitions and confines in order to give their lives an illusion of meta-narrative coherence. This is the kind of fan embodied in a wrestling clip I’m constantly thinking about, from one of the first episodes of the gentrified Sci-Fi Channel reboot of ECW, where Sandman beats the shit out of a masked jabroni dubbed “Macho Libre,” making explicit the venomous white-man-Michael-Douglas-in-Falling Down-esque-rage that so often sits at the core of American marks’ antagonism toward “foreign” wrestling styles.

But as a form that cannot be entirely predicted and cannot be entirely improvised either, and one that cannot exist without the human body, wrestling is everything but stable or solid or safe: it is fluid and changing, living and dying, breathing and bleeding, and it is wherever the body goes. Lucha libre in particular, though it has such a cultural specificity and defined genre tropes, is wrestling at its most physically unpredictable: the desire of literal artists like El Hijo Del Vikingo to consistently stretch the limits of human athletic ability to the almost inhuman; the gender-bending and binary-blurring of exoticos; the intense and almost inseparable intertwining of a living artform and folk culture so often exhibited in street murals and bootleg merchandise with a deeply commercialized industry where “Corona” is the biggest word on the mat, a carousel of ads play behind the performers, and branded multi-verse cross-promotion with companies like Marvel are increasingly common.

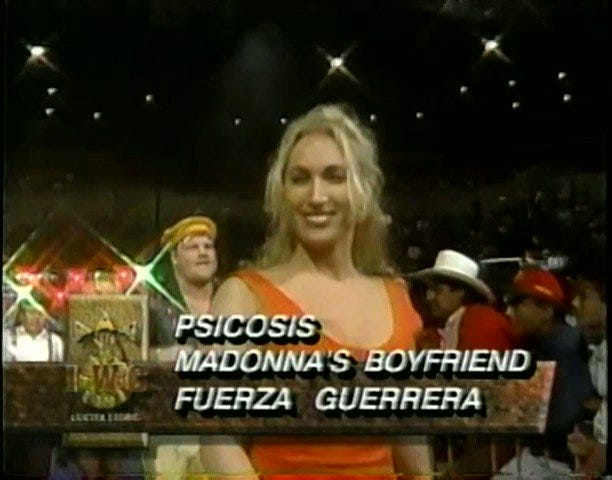

Lucha is so often synonymous in the United States with the high-flying cruiserweight innovation of Rey Mysterio, Jr., Juventud Guerrera, and Psicosis, introduced to a larger American audience outside of the Southwest for the first time thanks to ECW and then WCW. A brief “lucha boom” popped off in the United States in the mid-to-late 1990s, a subculture Turner first realized might have marketing potential with the historic AAA When Worlds Collide show at the Los Angeles Memorial Sports arena in 1994, the first time lucha libre was available to a national audience in the U.S. on PPV. That night was many American wrestling fans’ first formal introduction to legends like Eddie Guerrero, Rey Mysterio Jr., Psicosis, La Parka, El Hijo del Santo, Konnan, Octagon, and Perro Aguaya, as well as internationally prolific American workers like Chris Benoit, 2 Cold Scorpio, Art Barr, and the ever-underrated Louie Spicolli (then wrestling as Madonna’s Boyfriend, a gimmick in which he was an over-eager pop music stan who claimed to be Madonna’s boyfriend).

ECW would bring in those three pillars of 90s lucha — Mysterio, Juventud, and Psicosis — in addition to periodic appearances from rudos like Damian 666 and Super Crazy. Toward the end of the 1990s, both WWF & WCW tried to further capitalize on lucha, with McMahon and company launching the Spanish-language WWF Super Astros, a short-lived half-hour program of tapings featuring higher-profile AAA & CMLL talent like El Hijo del Santo and Negro Casas with younger jobbers and WWF wrestlers like The Hardys and Scotty 2 Hotty. WCW tried to fire back with Festival de Lucha, a television special that it had ambitions of selling as a full series to Telemundo to no avail, hardly unsurprising given WCW’s increasingly precarious existence in 1999. In the 21st century, aside from Mysterio’s run, fairly talented luchadores signed to WWE like Gran Metalik, Kalisto, and Sin Cara have mostly just been the butt of jokes.

Various attempts have been made at re-introducing American audiences to lucha libre, but all fairly short-lived. After Wrestling Society X, MTV took another shot at returning to its Rock N’ Wrestling roots in the early 2010s with Lucha Libre USA: Masked Warriors. Though it managed to get a minor action figure line, Lucha Libre USA only lasted one season on cable before shuffling off to Hulu and then dying. I still haven’t seen the show, but I’m curious to at some point: the roster included GOATS like Psicosis, Super Crazy, and Blue Demon, Jr.; indie up-and-comers like TJP (Sydistiko) and Rocky Romero (Azteko) working under gimmick; a “Chicas” roster with Awesome Kong and ODB; and Shane Helms for some reason. El Rey Network’s Lucha Underground found a much larger audience, and eventually placement at Netflix, and its influence on the current wrestling landscape is at this point undeniable, a pivotal training camp and source of exposure for the Lucha Brothers, Ricochet, Sw3rve, and countless more, as well as a laboratory for the cinematic cutscene visual style of COVID-era wrestling and EC3’s Rogan-brained Free The Narrative. If you were a new fan in the 2010s like me, LU was quite possibly your first exposure to what wrestling outside WWE could look like. Now the memory of Lucha Underground limps on, like the Janis Joplin biopic in 30 Rock that doesn’t have the rights to her life, as “Azteca Underground,” a zombie spin-off of Cort Bauer’s barely-making-money pit MLW. The lucha influence runs deep in so much contemporary American wrestling though, quite obviously in the style of indies like PWG and Chikara but more subtly in the style of new innovators like the Tiger Mask-meets-MF DOOM stylist Lee Moriarty, the top-shelf stunts of Dante Martin, or one of my favorite break-out stars of 2021, the extreme hardcore luchador Ninja Fuck Mack. Pretty much every tiny guy on the indies today owes their career to lucha libre, from Lio Rush to Nick Wayne to Starboy Charlie.

If we circle back to the 1990s and the Monday Night Wars, the most visible stage for luchadores in the United States was WCW’s cruiserweight division, a consistently golden trove of wrestling comfort food during the too-big-to-fail bloat of the Hollywood Hogan era. Disco Inferno notwithstanding, endless combinations of matches between Guerrero, Benoit, Jushin Liger, Malenko, Lionheart Jericho, Alex Wright, the aforementioned luchadores, and more are pretty much all classics. The cruiserweight belt has its origins in WCW’s earlier short-lived and paradoxically named “Light Heavyweight Division,” which was essentially just a mechanism to put Flyin’ Brian Pillman over, despite the fact that his weight wasn’t all that less than the Heavyweights, but lead to a string of underrated matches with strong workers like Ricky Steamboat, Liger, Ricky Morton, Brad Armstrong, Tracy Smothers, and Tom Zenk — before Scott Levy was the moody cultish Raven, he was the flamboyant Scotty Flamingo, who held the Light Heavyweight belt for a few weeks in the summer of 1992 before dropping it to Brad Armstrong, who vacated it after an injury, leaving the title dormant and never challenged for again. It’s really an enormous tragedy to me that Pillman was injured and his workrate diminished before he passed, because he would have absolutely shone in the cruiserweight era, and it’s hard to say if it would have even existed without his equally hard-hitting and high-flying matches — the first match on the first episode of WCW Monday Nitro, infamously filmed inside the Mall of America, set the stage for the cruiserweight revolution: frequent foes Brian Pillman and Jushin Liger, meeting once again in WCW after one of my favorite matches of all time from SuperBrawl 1992.

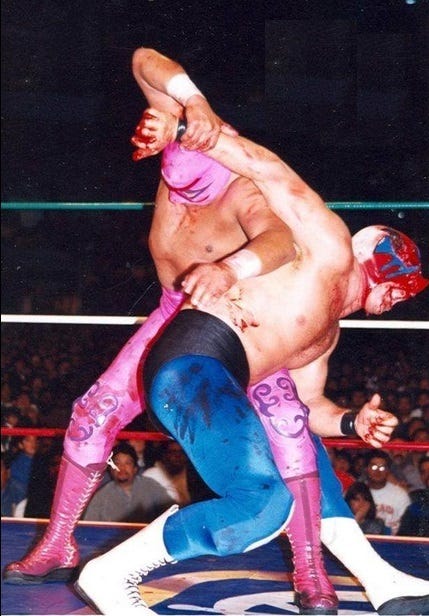

Every regional form of wrestling is its own spectrum of many styles, and lucha contains violent and frequently bloody multitudes — Psicosis spent Christmas Day 1995 in an arena in Mexico doing a barbed wire match in an ECW shirt, the only appropriate way to celebrate the birth of Jesus Christ and honor his eventual crucifixion, the original deathmatch spot of them all. More than American standardized pipeline products, lucha libre fully embraces one of the best attributes of wrestling, its allowance for an endless variety of body types. Lucha might conjure images of extreme sports-like stunt spots and high-flying dives, but it’s often just been two stocky, well-oiled men slugging each other to pieces. So it is with Atlantis versus Villano III, the only lucha match to have ever been voted Wrestling Observer’s Match of the Year. It is classically potent melodrama as only pro wrestling can do, with masks and legacies and bodies on the line, Atlantis one of CMLL’s top stars and Villano an indisputable legend of the game, about to hit 50 years of age.

The one thing that everyone knows and recognizes about lucha is the mask, a symbol of identity and honor that can be read for all kinds of sociopolitical analysis. When a wrestler wears a mask in lucha libre, it is a signifier of true anonymity, as they work only under their ring name, only a body and a voice with no government name or biographical details, a tier of celebrity nonetheless but often quite different from the fame of American “superstars,” somewhere between a superhero, a cartoon character, and a canonized saint. The mask can signify affiliation, whether one is a rudo or tecnico (heels and faces), cultural heritage, or even media fandom, as in the case of Rey Mysterio’s frequent allusions to comic books or Avatar in his ring-gear. In Rey’s early work with WCW, when the American viewing public and wrestling power-brokers were still largely skeptical of smaller workers, Mysterio’s employment of the Spider-Man mask almost feels like a way for Rey to suggest how we should interpret and respond to him. If you can relate to a more diminutive comic book superhero who is a “normal” guy, then you can root for the pint-sized underdog who does absolutely indescribable things with his body.

In a Mask vs. Mask match such as Atlantis vs. Villano III, which falls under the “Lucha De Apuestas” or “Bet Match” genre, the stakes are raised tremendously, as the mask comes to represent an entire body of work, an entire lifetime of sweat and sacrifice, and its loss signifies a very different kind of life. It means the risk of being known in the fullness of yourself for the whole crowd and world to see. There’s some obviously very potent metaphors for personal identity in the meaning of the mask, which I think is really artfully and thoroughly explored in Heather Levi’s amazing book The World of Lucha Libre, but I think is shown particularly powerfully in the recent Enjoy Wrestling Hair vs. Mask match between Edith Surreal and Ziggy Haim. These are two of my favorite newer workers on the indie scene, both in terms of presentation and physical skill, and also both very inspiring and exciting to me as a trans woman who loves to see kickass queer women in the ring. Edith Surreal has spoken about how, as a trans woman working in a very visible form, wrestling under a mask has allowed her to overcome fears and insecurities about being perceived and negotiating dysphoria as a public performer. Those are feelings I deal with a lot as someone with a public platform in my writing and on social media, and I can’t imagine how much more intense it must be to feel so seen as a trans woman in such a physically demanding and public setting, where your body can sometimes be the subject of judgment. By putting her mask on the line, Edith risks the security and refuge that so trans and queer people find in anonymity — think of, say, trans artists like SOPHIE existing under mysterious blurred identities before feeling comfortably showing their face to the world. It is, at least for me personally as a trans woman, the highest stakes of any Lucha De Apuestas match I’ve ever seen. Edith recently paid tribute to Chris Kanyon with Mortis-themed ring-gear, and Kanyon talks explicitly in his book about the Mortis character and costume providing a shield for his fears of living openly outside the closet.

This is a very long road leading us back to this lucha classic, which a bunch of doofuses on Cagematch think is overrated, some shit that is of course bound to happen with basically anything that gets canonized by WON—some of which is genuinely overrated, but a lot of, particularly from the early years of the newsletter, is often formative and fascinating if not genuinely great ring-work. As we all know, Meltzer and his acolytes have their significant blind spots, and lucha is one of them, though it’s improved ever so slightly and a lot of that has to do with the endless series of availability and distribution issues lucha promotions have faced in the United States—most recently the legal dispute between AAA and Lucha Underground.

There are dives in this match weaponized strategically and precisely for maximum crowd pop, like a good jump scare, but this match is significantly stiffer, bloodier, and more submission-based than you might anticipate from lucha. It’s one of the hottest crowds I’ve ever seen, people of all ages and genders and classes absolutely popping for tough legends almost evenly matched in their form and body type, that kind of solid beef strongman frame that you don’t really see on wrestlers anymore except for, like, Colt Cabana or Big E. It’s an all-out torturous affair of stretching and locking from the immediate jump, which reminds you that, as Bret Hart says in his memoir, that Konnan was the one who taught him the scorpion lock that transformed into the sharpshooter. In between brawls and out-right pummeling that spills out of the ring, Atlantis and Villano keep twisting each other into all kinds of impossible combinations, just like their legacies and careers are intertwined in this moment of mutual risk and assured brutality—each man is equally invested in the outcome, in terms of what they put their bodies through, in terms of what is on the line and what this represents, and in their families looking on in wondrous fear and awe. At one point, an angel of a doctor dressed in saintly white rushes in from the wings of the stadium to check the men.

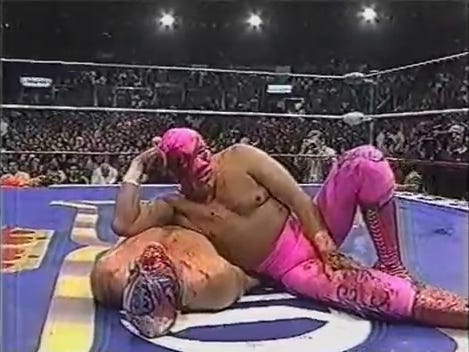

Here we see the mask not as a symbol, not even as a mask really as it is normally conceived: a disguise, a shield, a cloak, a barrier. I mean that figuratively, as the sacrifice of body and career is signified in the potential sacrifice of the mask, makes the mask synonymous with something so much larger than a piece of cloth and string. But I also mean it more literally, because the mask immediately becomes both a hindrance and a weapon. While the mask might be something respected like a flag, it is also consistently ruined and desecrated, torn to bits, with blood droplets begging to bust out of the seams. Juice pools inside the mask of Atlantis and turns it from a strong blue to a gray and darkened mush, blood and sweat blinding his vision and reducing his blows to pure Force-like instinct, the very thing he is fighting to save obstructing his ability to fight. Less “color” and more the chocolate syrup goop that Hitchcock used in the Psycho shower scene. There’s an absolutely sickening moment where Villano starts flicking near his eyeball, presumably to free up the blood that’s filling up his mask and getting in his eyes. The mask almost does not stand for anything at all; it becomes synonymous and fused with the wrestler wearing it, another layer of exposed skin that offers some kind of protection but is also vulnerable. As they told us in biology class, the epidermis is the largest organ; we humans don’t have an exoskeleton, but a vulnerable membrane that is easily bruised and cut and offers so little in the way of evolutionary protection. The mask, like the skin, is an organ worn on the outside that can be wounded.

When Atlantis secures the win, it is almost a moment of relief for Villano, like a snake preparing to shed a skin that’s grown dry and old, his moment of painful endurance now over. Forsaking the mask does not mean your career is over — Villano III kept wrestling for years until his death in 2018; Dr. Wagner, Jr. and Psycho Clown are both now GCW regulars after Psycho Clown took his mask at Triplemania 25; Rey Mysterio lost his mask to Kevin Nash and then changed the spelling of his name so he could get it back without violating lucha code. As is so clear in the post-match interview, in which Villano’s mask is undone and removed, his pock-marked and bladed face shown for the first time, his family now publicly embraced, and his true name — Arturo Mendoza — finally in the public record, there is a kind of liberation almost. It is quite literally a coming out, and coming out brings its hints of bittersweet sadness and tragic grief along with immense relief and freedom. Arturo is now free of a piece of skin turned into crusty scab, no longer trapped in a cloth cage drowning in his dripping sweat and blood, the truth of his face touching the open air for the first time. Though the athletic abilities of wrestlers are so often almost inhuman, they are still very human, but treated by so many like animated puppets on a screen or actors in the distance, whose labor is unrecognized, whose injuries are minimized, whose autonomy is so often overwritten by employers and promoters who exploit and fans who take for granted. To be free of the mask, is to be free of being seen as superhuman and infallible and the impossible expectations of industry and audience, to let others know that you age and suffer and struggle like all the rest of us. As Hank Williams, Jr. put it — perhaps the Villano III, Jr. to his father’s Villano III — Arturo Mendoza no longer has to be a legend, now he can just be a man. Masks don’t protect you after all; they just hide the scars so no one can see.

Matches discussed in this piece / RIYL:

Flyin’ Brian Pillman vs. Jushin “Thunder” Liger (WCW Superbrawl II, 1992)

El Hijo del Santo & Octagon vs. Eddy Guerrero & Love Machine/Art Barr (Mask vs. Hairs 2 Out of 3 Falls Tag Match (AAA When Worlds Collide, 1994)

Flyin’ Brian Pillman vs. Jushin “Thunder” Liger (WCW Monday Nitro #1, 1995)

Rey Mysterio, Jr. vs. Juventud Guerrera (Two Out Of Three Falls Match) (ECW Big Ass Extreme Bash, 1996)

Rey Mysterio, Jr. vs. Psicosis (WCW Bash at the Beach 1996)

Dean Malenko vs. Rey Mysterio Jr. (WCW Great American Bash 1996)

Rey Mysterio, Jr. vs. Ultimo Dragon (WCW World War 3, 1996)

Psicosis & Halloween vs. Ultraman 2000 & Leon Negro (Barbed Wire Street Fight) (AAA, 1995)

Atlantis vs. Villano III (Mask vs. Mask Match) (CMLL, 2000)

Psycho Clown vs. Dr. Wagner, Jr. (AAA Triplemania XXV, 2017)

Killshot vs. Dante Fox (Hell of War Match) (Lucha Underground Ultima Lucha Tres, 2017)

Alex Zayne vs. Ninja Mack vs. Lio Rush Triple Threat Match (GCW Fight Club, 2021)

Edith Surreal vs. Ziggy Haim (Mask vs. Hair Match) (Enjoy Wrestling Night Moves, 2021)

Dante Martin & Lio Rush vs. Matt Sydal & Lee Moriarty (AEW Dynamite, 2021)

Team Bandido (ASF, Bandido, Laredo Kid) vs. Team Gringo (Arez, Demonic Flamita, Gringo Loco) (The WRLD on GCW, 2022)

![Lucha Clasica Ep. 4 - Villano III vs. Atlantis [Patreon Only] - LuchaWorld.com Lucha Clasica Ep. 4 - Villano III vs. Atlantis [Patreon Only] - LuchaWorld.com](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!RpX0!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb751bfee-d90e-41f3-9ffc-eddba2aca33a_520x293.jpeg)