bill goldberg vs. satoshi kojima (all japan pro wrestling, 2002)

the first installment in my new wrasslin newsletter HOUSE OF 1000 MARKS

welcome to my attempt at a wrestling newsletter… don’t call it a dirtsheet. i’m notoriously bad at following through at creative projects like this but i’m hoping to write about at least one match a week, with other wrasslin takes mixed in there, though not all of them will be 2k manifestos about goldberg, some will probably be very to the point. if u sign up for the paid tier you get extra match recommendations every month as well as ~exclusive~ download links to rare matches & shows from my personal archive. this is… HOUSE OF 1000 MARKS

Bill Goldberg vs. Satoshi Kojima (AJPW Royal Road 30 Giant Battle 2nd, 08/30/2002)

Whereas so many marks, smarks, and violence enthusiasts grew to love pro wrestling in their childhood years, clouded with nostalgic affection for the Attitude & Ruthless Aggression eras, I came into wrestling with virgin eyes in the year 2016. My wrestling origin story is roughly this: I had little opinion on it until I started noticing GIFs and clips from mutuals on Twitter of Japanese wrestlers & indie workers doing absolutely incredible and sometimes absurd things with their bodies. The little perception of pro wrestling I did have was mostly from kids at my elementary school wearing Stone Cold shirts or nWo wristbands, and later on the acting work of Dwayne Johnson and John Cena, so seeing someone like Shinsuke Nakamura and finding out about entire worlds of melodramatic combat that I’d never knew existed felt a little bit like listening to Young Thug and Future mixtapes around the same time.

Seeing GIFs eventually led to watching what I could find, pulling up DailyMotion clips that I didn’t really have context for with names like “Wrestle Kingdom” and “Joey Janela’s Spring Break” before eventually seeking out the most accessible & mainstream wrestling product that I could wrap my head around: WWE. Some friends and I, all new to the medium, got together to watch that year’s Royal Rumble, which had just happened a few days previously. From there, I spent maybe a year as a committed WWE fan—using the logic of “poptimism” to excuse my not going any further than the Disney of wrestling, which was mostly out of intimidation of how much wrestling exists, how daunting and alienating the community around it can be, and a fear it would eat up all my time—until I got burned out and went into a lapsed state, as almost every fan inevitably does. Every year I’d watch the Rumble and WrestleMania, keeping up here and there with news or notable matches on Twitter, but it wasn’t until early 2021 that wrestling became one of my primary loves and obsessions. And all it took was taking one glimpse outside WWE, dipping my toes into the endless pool of styles and formats that have existed throughout the history of recorded & broadcast pro wrestling, to hook me. Once I realized the multitudes that wrestling contains, the way it intersects with pop culture and geopolitics and capitalism and a thousand other layers of potential analysis and personal fascination for me, the art form pinned me to its canvas.

I’ve been aiming to start writing about wrestling in newsletter form for what feels like ages now, but I was struggling with where to begin, what match could possibly stand as some kind of thesis statement for how I approach wrestling and what I want to capture in my take on it. Though I watched it without any intention of taking a further look, Goldberg vs. Satoshi Kojima from AJPW 2002 feels in some ways a perfect object, the kind of thing I went into student loan debt in order to call a “rich text.” Goldberg is locked up with my memories of getting into WWE, and the early frustrations I began to feel with the product.

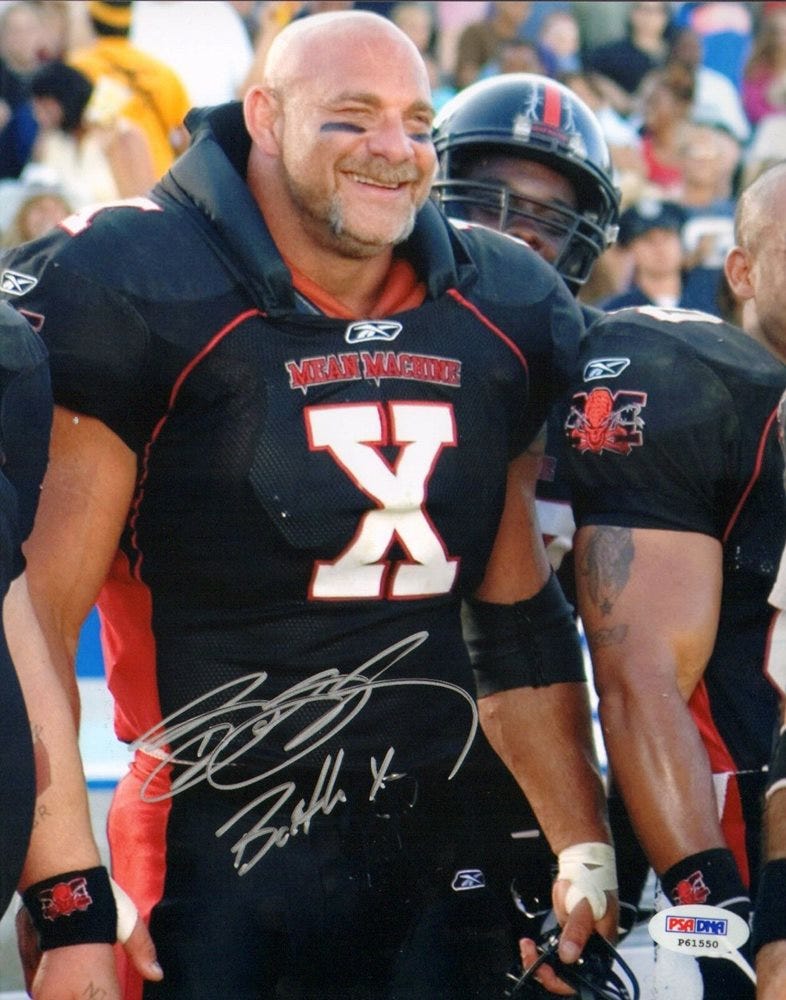

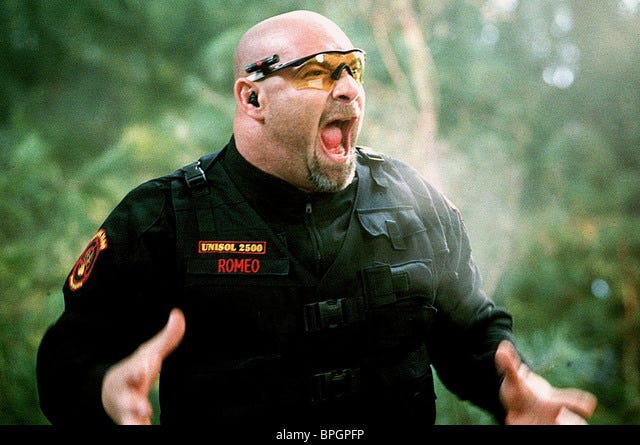

If it was the debut of AJ Styles at the 2016 Royal Rumble that solidified my interest in WWE, it was the return of Goldberg that signaled the beginning of the end of my consistent patronage of Titan Towers. In case you’ve repressed your memories of that time, the mid-2010s was a remarkable period of optimism for WWE fans, with Daniel Bryan’s insurgent YES! movement; the boom of NXT leading to the eventual main roster debuts of indie veterans-turned-superstars like Kevin Owens, Sami Zayn, Samoa Joe, & Nakamura; and the Women’s Revolution embodied in Bayley, Becky Lynch, Charlotte Flair, & Sasha Banks. Of course, we don’t really need to know what happened next, as WWE squandered all goodwill and potential as it always does, turning Bayley and Sami into stooges, turning Charlotte into the female Hogan, doing who knows what with Shinsuke Nakamura, and sacking Samoa Joe several times over. Goldberg in one figure symbolized to me at the time all that was wrong with the product, a continued insistence on snuffing out everything youthful and inventive in favor of putting over an aging name brand almost vindictively. There was no dynamism or physical inventiveness, and hardly any melodramatic drive, to the blue-balled squash matches of a crumbling WCW star that as a novice fan I hardly knew beyond bit parts in The Longest Yard and Universal Soldier 2.

Goldberg is at once complex and very simple in terms of his appeal. What’s direct about him is the appeal of his in-ring work and character: he’s a squash artist, who works in blunt maneuvers and stiff slams, while more critically acclaimed wrestlers create long chains of movement. Or, in more disparaging terms, he is traditionally perceived as a one-trick pony, who comes out and does the Jackhammer and Spear and then goes home. But his appeal as a gimmick and star persona is a little bit more layered: for a time, he became something of a crossover pop culture icon, which is curious given that he’s not really known for mic skills or a colorful personality, the attributes that generally most attract non-fans to wrestling stars. He’s literally famous for being fucking tough and big and mean, but in a way that wasn’t ever necessarily out-right villainous or unnaturally heelish; you wanted to see him destroy shit because he looked so fucking cool hopping into a Jeep and walking in a Harley Davidson jacket around surrounded by a posse of Marines for some reason. This is a man made of metal, a man who walks through sparks.

There’s almost a minimalism to his appeal, even as much as he is a wrestler who could not exist without the big-budget spectacle and pyrotechnics of televised sports entertainment, which is what makes it all the more layered for me, since wrestling as a medium is so often perceived as maximalist: the lone elbow pad, the single tribal tattoo, the lacquered-up shine of his physique. Goldberg is pure uncut product, in one word, in one human being. So many WCW stars were recycled, whether repurposed WWF main eventers or recruits from ECW and around the world, but Goldberg was probably the biggest “developmental” star Turner ever churned out, a pure product of Atlanta’s Power Plant. The great irony of the outcome of the Monday Night Wars is that while WCW has been written out of the narrative and WWE uses its in-house propaganda wing to disparage the former competition at every turn, McMahon’s playbook over the last two decades has cribbed so much from the opposition’s tactics. Goldberg was tainted enough by his time with WCW in the eyes of Titan Sports that they would not pick up his contract from Time-Warner, but he’s become one of the last strong brand pillars of WWE in the contemporary period. He would in many ways serve as the prototype of the ideal WWE star, a pure hunk of athletic flesh that could be shaped into a sports entertaining crossover pop culture icon with no allegiance to family, the territories, or The Business, just fealty to the corporate overlord who promises primetime stardom in exchange for several pounds of your flesh and 300 days out of your year. Whereas someone like Bret Hart has been beloved in part because of his support of “The Boys,” Goldberg is tarnished in certain corners of wrestling fandom because he so transparently has only cared about The Boss or the bottom line — perhaps like the Ultimate Warrior of WCW, a strong tough guy who made it to the top despite basically being an outsider to the business with something of an active disdain for wrestling and a hostility to the rest of the locker room. That sense of entitlement and resentment manifests in his unwillingness to sell for fellow workers and his notorious disregard for their physical safety in the ring — most infamously in his injury of The Hitman.

If Vince could have his way, Sports Entertainers would be born in a test-tube laboratory, like Jango Fett’s infinitude of clones, with no sense of self beyond duty and no human needs. The company’s recently announced NCAA-to-sports entertainment pipeline program “NIL: Next In Line” is just the latest in a long history of trying to engineer future WWE superstars in a controlled environment outside the normal training grounds of pro wrestling. It’s only fitting that Goldberg would return a decade later after his brief run with The Fed to become one of the crown jewels (pun intended) of Vince’s collection, because he is the kind of performer Vince has always longed to create, a worker with the physical presence and athletic background of The Rock or Roman Reigns, without the family history or any other allegiances. Goldberg is one of the few human beings absurd & titanic enough to carry a belt dubbed “The Universal Championship” as if he was actually out there defending the title on behalf of Planet Earth, as close to a monster as a human being can get while still maintaining a slice of realism. He’s also something of a “himbo, in today’s parlance—the tribal tattoo around his arm is like the alpha male version of a tramp stamp.

Goldberg transcends a Meltzerian paradigm of workrate; he can never truly be condensed to a Cagematch rating simply because so many of his matches clock in at under 5 minutes. This is what finally brings me back to the specific match I’ve chosen to examine, Goldberg’s debut in Japan and his first match since Turner’s divestment from the wrestling business. Of the 12 minute runtime on YouTube, only around 4 ½ minutes are the actual match, with just as long given to Goldberg’s entrance and the post-match interviews.

In classic puro fashion we follow Goldberg backstage as he enters the ring, which can often endow Japanese wrestling with a kind of documentary affect, but with a figure like Goldberg it all feels patently absurd. In his match against Rick Steiner in All Japan a few years later, Goldberg hops out of a van in a beanie and motorcycle jacket, shuffling through dark streets to the Tokyo Dome like he’s in a Bourne movie. There’s a very weird series of moments where Goldberg keeps holding objects in his mouth—two members of his squadron help him disrobe as he bites onto his gloves, and then later he puts a rather large roll of grip tape in his mouth as he prepares his hands to do violence, which somehow adds another level of weird menace, as if he’s trying to prove that he could easily chomp your dick off. As he enters his dressing room, he shoves out the camera crew and slams the door in their face, channeling his best Stan Hansen.

The entrance for the 2002 Kojima match is more tame by comparison, with Goldberg flanked by what look like Guardian Angels as he walks down the long hallway sullen in thought, his Command & Conquer menu-ass entrance music resounding through the arena. There’s a single-mindedness to Goldberg’s aggression and shtick that makes him a perfect gaijin, because he needs no language other than the sheer force of his fists and the menace striking out from his eyes. His size and the uncanny smoothness of his body says that he is an inhuman invader before he even opens his mouth to bark and cuss. The aura is classic Goldberg, but when he’s in the ring, the work is markedly different from his American performances, and he even acknowledges it in the post-match, asking a reporter if he was still over with the crowd despite not using his trademark jack-hammer or spear.

In the first 90 seconds after the bell rings, Goldberg and Kojima only make physical contact twice, two brief lock-ups followed by Goldberg painfully slamming Kojima to the mat with a thick crash, hunter and prey circling each other as Goldberg chooses violence with his eyes. Kojima comes at Goldberg with a few chops that Goldberg doesn’t even attempt to sell, before swatting Kojima away, who then takes an almost pratfall-like tumbling bump into the ropes and out of the ring. When Kojima gets back in the ring and they lock up again, Goldberg rolls him into a leg-lock and just starts stretching the fuck out of his leg, the literal dictionary definition of “hyper-extension.” The physical destruction is still the same, but it’s this series of relatively simple physical exchanges and moves that completely opened my third eye and pilled me to Goldberg, as he demonstrates a gaijin grappler side of himself I’d never imagined. His run in Japan was limited, but I honestly lay awake at night now dreaming of Inokiist Goldberg, or Pancrase Goldberg, or Goldberg & Lesnar in 2004 doing some kind of modern MMA daddy Miracle-Violence Connection. Technical Goldberg. Scientific Goldberg. Cerebral Assassin Goldberg. Malenko Goldberg.

It’s this completely different side of a worker I thought I knew and understood that feels like such a useful starting point for getting more analytical about wrestling in this newsletter. Wrestling contains so many endless multitudes, so many countless match-ups in who knows how many forgotten promotions, that it is almost to truly understand it to, to fully take in the entire ~oeuvre~ of a wrestler in the way we might with another artist. But that’s also what I absolutely love about wrestling: it is full of endless contradictions and endless revelations alike, a form that’s constantly shifting and literally in negotiation with itself as two people collaborate together to work on something that can only exist beyond the individual—there is no wrestling with just the self. To watch one match in isolation is extremely different than absorbing a more full body of work, and wrestlers so often contain shades and contours unseen if you’ve only encountered them in one arena or outlet. To see Hollywood Hogan in his “Voodoo Child” Venom-like gritty heel phase versus the Hulkster in his ketchup-and-mustard real-American Mega-Powers garb is like encountering different periods of Picasso; watching the “Loose Cannon” era doesn’t give you a full understanding of quite how revolutionary Brian Pillman was as a physical performer and athlete in the early ‘90s; the fan-favorite insurgent Daniel Bryan of the WWE is very different from the blood-ready American Dragon submission master of the indies and AEW.

Though it is so awfully preserved and so rarely taken seriously as a historical form, wrestling is all about a kind of research and study, even on the level of the work itself. “Watching tape” as an athlete is in some ways not all that different from digging into the archive in a more obviously scholarly sense. There’s always another match to be viewed in order to understand another performer’s technique or to better understand yourself, and always much knowledge to be absorbed in a medium that is quite literally physically alive and evolving just as the human body does. Wrestling is a breathing, flesh-and-blood art form in a way almost nothing else could ever be—while some performance and visual artists may choose to shed blood or incorporate bodily fluids, wrestlers have no choice but to explicitly put their bodies on the line, because there is nothing to wrestling without the human physical form, something that is constantly in a state of change although it so often appears stable. Maybe someday we’ll have robot combat but wrestling is one form of labor that could never really be automated. Even when the bell rings, the work never ends, because the body is the work, and the body keeps on living.

coming soon (hopefully):

my favorite matches of 2021

some thoughts on AEW revolution 2022

a reflection on how american TV wrestling fundamentally changed in 1996, as i continue to work my way thru every major american wrestling super-card/PPV

No Holds Barred vs. Ready To Rumble: wrestling’s two most infamous hollywood vehicles and their unique but equally weird depictions of The Business

why i absolutely love the Lord Steven Regal vs. Belfast Bruiser storyline from WCW 1996, one of weirdly most woke wrestling angles ever

getting Antonio Inoki-Pilled

my first paid subscriber drop is gonna be a match pack of some deep cuts from my boy genichiro tenryu, who i have started to feel is lowkey the jeff jarrett of japan. i will explain this more at a later date